The Grail Castle and its Mysteries

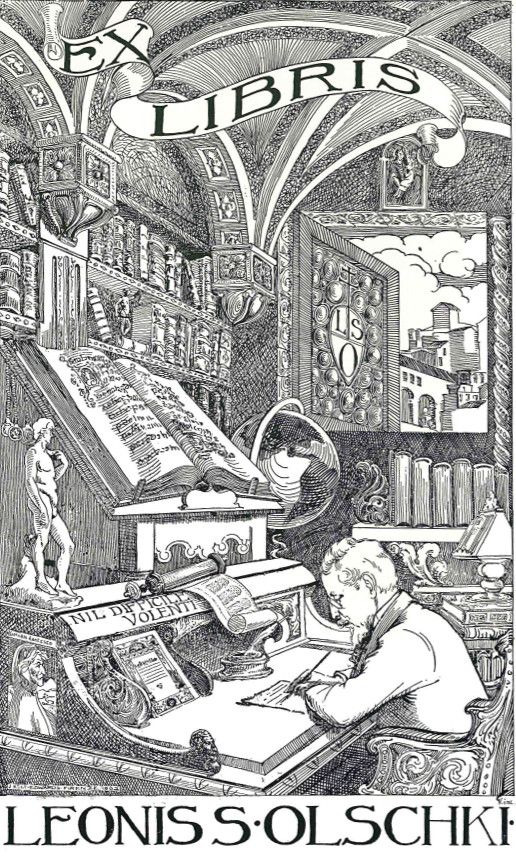

by Leonardo Olschki.

Translated from the Italian by J A Scott and edited, with a foreword, by Eugène Vinaver.

Manchester University Press, 1966.

Graal: “scutella lata et aliquantulum profunda in qua preciosae dapes divitibus solent apponi gradatim, unus morsellus post alium in diversis ordinibus” (a wide and deep saucer, in which precious food is ceremoniously presented, one piece at a time in sundry rows)

— Helinand de Froidmont (early 13th century)

If you were thinking the mysteries of the grail castle were to do with long-lost holy relics, Last Supper chalices, magical stones, Celtic cauldrons, secret occult societies, witches, extraterrestrial visitors or even the blood of Christ you will need to look elsewhere. (There are whole libraries in Babel to cater for each and every taste in such mysteries.)

First published in 1961 as Il castello del Re Pescatore e i suoi misteri nel Conte del Graal di Chrétien de Troyes (‘The Castle of the Fisher King and its mysteries in Chrétien de Troyes’ The Story of the Grail’) this is not a publication aimed at a popular market: with a foreword by a foremost Arthurian scholar, key extracts from the medieval romance in the original French, and furnished with footnotes, endnotes and a select bibliography, this monograph (less than a hundred pages) is very much a closely argued academic paper from someone very familiar with the literature and theology of the period in question.

The author also effectively — though very politely — demolishes alternative theories from his fellow scholars as to the nature of those mysteries.

To begin at the beginning: Le Conte del Graal is the very first medieval romance to mention the grail, or graal. The inexperienced but impetuous young ingénu, Perceval, finds his way to a mysterious castle, directed there by a noble fisherman in a boat. Whilst being treated to a banquet in the castle hall he witnesses a procession in which young men and women carry curious objects to a side chamber: a vaslet or squire bearing a lance that bleeds, two more squires with candelabras, a maiden with a glittering receptacle, called a graal, and finally a maiden carrying a silver tailleor or platter. Because he has been advised not to ask too many questions he refrains from asking what the procession signifies, and in the morning wakes to discover the castle completely deserted, with nobody answering his calls.

This procession, the objects, the graal, and the person they were intended to serve (the Fisher King? The Fisher King’s father?) were all so intriguing, and Chrétien seemed so reluctant to explain them, that in a few short years his unfinished poem was by other hands continued, translated, elucidated, elaborated and eventually interpreted by a great many writers and theorists, all of whom pretty much flatly contradicted each other. Later concepts — transubstantiation and the Corpus Christi feast, survival of cults and an Old Religion, reincarnation and holy bloodlines — were anachronistically grafted onto the whole grail complex.

But Olschki simply suggests (but in meticulous detail) that only familiarity with late 12th-century thinking will help explain what the significance of it all is, and it doesn’t involve the chalice of the Last Supper:

The whole ‘procession’ in fact takes place in a completely secular setting. There is no cross, no liturgical gesture, not one single religious figure to accompany the supposed relics of Christ’s Passion. From the ecclesiastical and orthodox point of view, the procession is even sacrilegious, for it is an accessory to a banquet — in other words, almost a caricature. It is therefore astonishing to think that critics can persist in their wish to interpret it as the Christian initiation of an ignorant young knight and as a fanciful expression of the poet’s religious feelings. [p 13]

In short, Olschki’s discussion of dualistic Gnostic and Manichaean traditions (as contrasted with more orthodox Catholic doctrines) makes it clear that the medieval poet was giving not so covert references to heretical Cathar teachings and practices as supported by certain nobles in this grail procession. The host or wafer that Perceval is later told is served to the Fisher King in the castle “brings to mind the consecrated bread that was broken and distributed to the faithful in the sacramental banquets that constituted the sole ceremony normally celebrated by Catharist communities […] unaccompanied by any priest, altar, or any other rite…”

Olschki, of course, doesn’t follow the extreme theories that his contemporaries put forward about French Cathars and sacred objects being smuggled to safety, or of cults that survived in the Pyrenees to this day, or of reincarnation being the key to finding out about medieval Catharism. However, the things that happen to Perceval subsequent to his one and only visit to the castle all strongly lend weight to Olschki’s suggestion that the young knight is being schooled back into orthodox Christian beliefs.

Unfortunately we will never know how Chrétien intended to complete his romance (the unfinished text ends in the middle of some of Gawain’s adventures) but the textual clues all point to Perceval, who had once mistaken King Arthur’s knights for angels, being returned to the Catholic fold.

This won’t, of course, please the romantics among us who would love to have a mystery more imaginatively explained. But human nature tends to go with the reasoning encapsulated in the famous quote from the 1962 film, The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance: “When the legend becomes fact, print the legend.”

‘When legend becomes fact’ was first published 22nd September 2018 in my Calmgrove blog.

On the original post Jean of Howling Frog Books wrote “When I read it in college, my prof drew connections between the Grail procession and Passover, with the youngest child’s job of asking the right questions.” I replied “I’ve read this suggestion before, I think in Emma Jung’s psychological examination The Grail Legend. The difficulty with (and simultaneously the delight in) the grail quest motif erupting into medieval consciousness is that it borrows from or offers parallels with so many other practices and cultures, so much so that one can propose any one of many ‘origins’ for it.

“And of course one can take one’s pick from half a dozen versions of the grail story that appeared within half a century of Chretian’s romance, use that as one’s urtext and then prove one’s theory to one’s heart’s content! Katherine Maltwood in the 30s even used the 13th-century Perlesvaus to propose a prehistoric Temple of the Stars laid out in giant zodiacal effigies in the landscape around Glastonbury, and others have imagined the grail as an extraterrestrial source of power, and so it goes on.

“Your point about the Passover question is suggestive, however, Jean: much of Le Conte del Graal and subsequent texts emphasise the importance of family relationships and the recognition of familial ties and responsibilities. But then, don’t most communities emphasise these in their lore and their rituals?”

In answer to Lynden Wade‘s query about ‘grailology’ as a word I wrote “Whether or not Grailology is a word (and as C S Lewis uses it, even claiming he made it up – as discussed hereⁿ – I suppose it is a real word!) it does describe a specialism that many scholars lay claim to. Personally I’d prefer a term more rooted in classical roots, like ‘gradalology’ perhaps, but I don’t somehow think that’s going to catch on!”