We were almost bent double getting to the front doors; for safety the car had been parked with its wheel right up to the kerb.

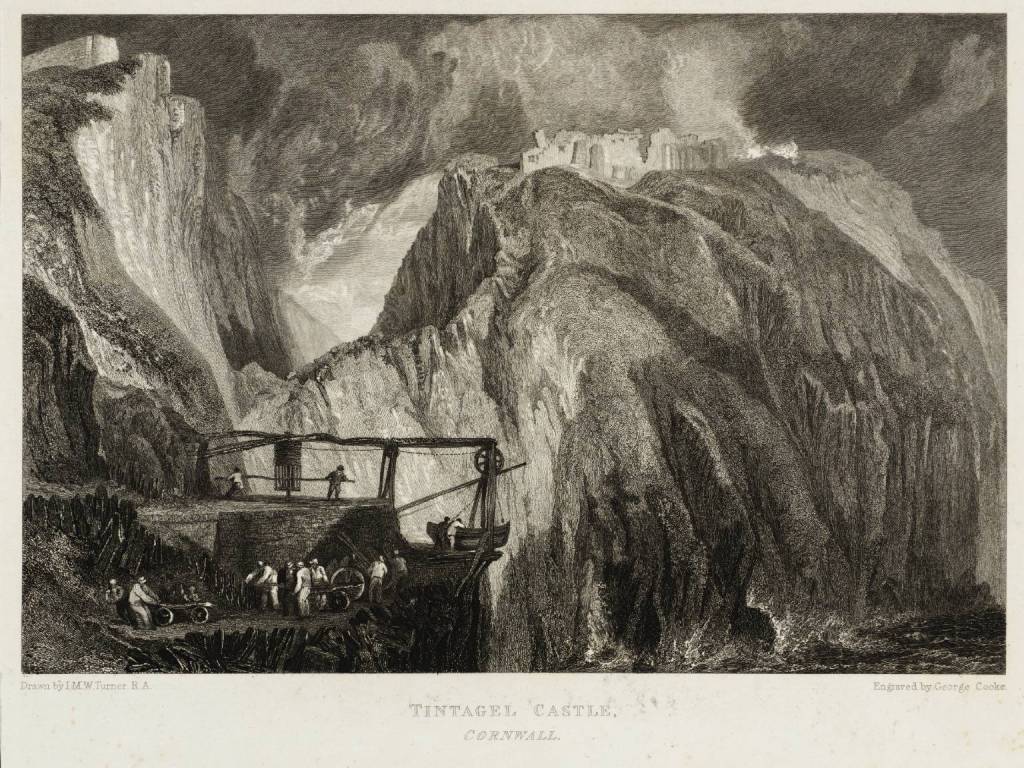

Having inveigled a stay at the Camelot Castle Hotel at Tintagel (King Arthur’s Castle Hotel as was), we had forgotten how unremitting the winter weather was in North Cornwall. From our four-poster bed we might have had views of Tintagel Castle, if the squalls had allowed, but they didn’t and so we didn’t.

It brought home to me the perennial question, why would anyone have wanted to stay at Tintagel Castle in its heyday? Surely Arthur, king or otherwise, if he ever had residence there, must have asked himself the selfsame question?

Legend

Tintagel burst into the written record in Geoffrey of Monmouth’s History of the Kings of Britain (1136) as the place where Arthur was conceived by Uther Pendragon on Igraine, the wife of Gorlois, Duke of Cornwall (Gwrlais in Welsh). This was achieved by deception in a manner that — whether based on the story of the conception of Hercules (Russell 2005) or Alexander the Great (Lovegrove 2005) or on native tales (such as Pryderi’s story in the Mabinogion) — suggests legend rather than true history. Geoffrey may well have visited Tintagel because his description shows a familiarity with the constricted access to the so-called Island (now fast becoming a reality), but quite why he picked on this windswept site can only be speculated on (Lovegrove 2005: 10-11),

One way round the indubitably wintry inhospitality of Tintagel is to regard it as principally a summer residence, and this indeed is how it is viewed in Béroul’s 12th-century romance, Tristan. Post-dating Geoffrey’s Historia, it is possible that the earlier work influenced Béroul’s decision to place the summer stronghold of Tristan’s uncle King Mark and some of the story’s action here.

In the early 13th century, the wealthy second son of King John, Richard Earl of Cornwall, acquired the site of Tintagel, plainly with the intention of garnering some Arthurian glory to himself. He built much of the castle still visible today, sometime after he became Earl in 1227. (A decade or so later he was to found Hailes Abbey in Gloucestershire, later famous for its relic of the Holy Blood, and was elected “King of the Romans”, that is, King of Germany, in 1257 – clearly somebody concerned to be more than just a bit player in history). The remains of the castle (which was never really of military significance) cemented the later perception of Tintagel as being the site of the legendary King Arthur’s castle.

Archaeology

In the early 20th century local historian Henry Jenner opined that Tintagel “has singular little history and not much romance attached to it … Historically and romantically Tintagel Castle is rather a fraud” (Jenner 1996: 36).

However, he also speculated that Tintagel Island “may have become a religious establishment of Celtic saints or monks at a later period, and the presence of the evidently Celtic chapel of St Ulyet or Julitta and of Christian interments of perhaps the 5th or 6th century, and the fact that it came into the possession of the monks of St Petrock’s, Bodmin, seem to indicate something of the sort…” But he then goes on to insist that “all this must needs be pure conjecture. The evidence is very slight” (Jenner 1996: 25).

This “very slight evidence” was taken up enthusiastically by the late Ralegh Radford in the 1930s. He maintained that in his excavations he had indeed discovered the Dark Age Celtic monastery, evidenced by the widespread disposal of sherds of imported pottery from the Mediterranean all over the site. Many of the structures he uncovered were interpreted as Dark Age monks’ cells and associated buildings, and such was his undoubted erudition and authority that few doubted his findings, publicly at least.

In 1973, however, Ian Burrow delivered a lecture in which Radford’s 1935 interpretation was challenged by the proposition that the site was actually an early medieval secular site, a military stronghold as legend had insisted all along (Thomas 1994: 74). Even so, Radford maintained his belief in the purely religious associations in his co-authored booklet Arthurian Sites in the West published in 1974.

But it was to be a fire on the island in the summer of 1983 that really put paid to the monastic theory. Underneath Radford’s “Dark Age” monastic cells were revealed the traces of earlier structures, clearly associated with the ubiquitous Dark Age Mediterranean pottery. Many of Radford’s structures, which overlay the Dark Age features, were now identified as medieval, probably 11th-century, and not post-Roman.

In 1986 the new official guidebook to the site, by Charles Thomas, officially established Tintagel as a genuine 5th/6th-century high-status stronghold. In 1990 a team led by Christopher Morris, then Professor of Archaeology at the University of Glasgow and now Emeritus Professor of Archaeology at the University, began a new series of investigations on the Island, while a small team under Charles Thomas investigated the churchyard of St Materiana on the “mainland” opposite (eg Nowakowski & Thomas 1990). A more accurate modern assessment of Dark Age Tintagel was now underway, revealing the promontory site, protected by a Great Ditch, to be principally occupied not by monks but by the entourage of powerful local leaders with substantial manpower; one of these also had the authority to encourage the import of Mediterranean goods in the form of perhaps the largest assemblage of wine amphorae, tableware and glassware in all of Western Britain.

Interpretation

If Tintagel was indeed occupied in the Dark Ages, even if only seasonally, then who were these powerful leaders? As Neil Faulkner (2009: 29) puts it, “Perhaps the Arthur enthusiasts have captured a kernel of truth about Tintagel: it seems likely that it was a seat of power of the very type of Dark Age warlord from which the whole Arthur legend derives”.

First, we may probably discount King Teudar, who features as the adversary of local Celtic saints in medieval sources. His centre of operations, in any case, was further south, in west Cornwall around St Ives and the Hayle estuary.

The Life of St Samson mentions the 6th-century saint’s encounter with a local leader of a warband called Guedianus, who is referred to as the comes or count in Trigg, the district which included the site of Tintagel (Thomas 1994, chapter 14 passim). However, the Life seems to locate the Guedianus incident across the River Camel, rather to the east of Tintagel.

We now come to the King Mark of the romances, uncle of Tristan and husband of Iseult, Tristan’s lover, whose summer residence is named as Tintagel. Now, Gregory of Tours’ 6th-century History of the Franks notes a Breton king Chonomoris who, as Quonomorus, is identified by the late 9th-century Life of St Paul Aurelian as Marcus, king of Dumnonia, whom the saint meets in the Fowey area in south Cornwall. And, lo and behold, in the Fowey area is still located a stone with the names of Conomorus and his son Drustanus or Tristan. This, surely, is some sort of confirmation that Mark Conomorus, king of Dumnonia, ruled in Cornwall and may have lived at nearby Tintagel, surely?

However, Charles Thomas believes that “Mark is part of a three-way tangle between history, hagiography and epigraphy” throttling any attempt to identify him with the Cunomorus of the Tristan stone (Thomas 1994: 213). In any case, “the reference to Tintagel in relation to Mark as the king of Cornwall may have been a re-location” from Fowey to North Cornwall. There is no evidence, other than the romances, that Mark, or Conomorus (if they are really the same, or merely two individuals merged by the author of the Life of St Paul Aurelian) inhabited Tintagel, much as some writers would like it so (eg Ditmas 1969; Wilson 1999).

The genealogical manuscript known as Jesus 20 lists some kings of Dumnonia who appear to have ruled sequentially (Thomas 1994: 212): these are Gwrmawr (“Great Man”), followed by Tudwawl, Kynmawr (“Great Hound”, who might have been the Cunomorus of the Tristan Stone), Custennin (who might have been the Constantine in the Welsh Annals who apparently converted to Christianity around 589), Erbin and Gereint. We have no idea where these rulers, if they are all in fact genuine, were located other than somewhere in Dumnonia, that is modern Cornwall, Devon and possibly further east and north.

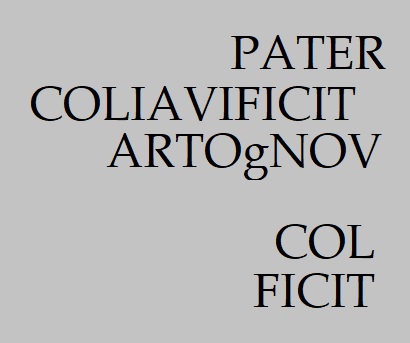

This leaves us the names found on the so-called Arthur Stone from Tintagel dramatically revealed to the world in a press release in August 1998. A slate drain cover from the east of the island was found to include part of a Late Roman inscription [1] on which was superimposed a series of 6th-century names: Paternus (or Paterninus), Coliavus and Artognou.

Coliavus, who appears twice, appears to have made or done something, as the word FICIT (the native version of classical FECIT) is associated with his name. What was made, or done? Does it refer to a contract, or even building work? Why was a Late Roman inscription chosen to attach the names to? These must have been individuals of some standing to have their names thus recorded.

The excavation team suggest that “it is difficult to envisage Tintagel as anything other than a site of the Dumnonian rulers … from which control could be maintained of passing shipping.” It is tempting to give these individuals some higher status at Tintagel.

Where did they end up? The answer might be, at Tintagel churchyard. Here, in 1990, the excavators revealed several Dark Age graves of indubitable Christian affiliation: some were cist graves, others unlined, at least two were mounded over, another was rock-cut, several had wooden grave markers and there was clear evidence for the raising of a granite pillar (Thomas 1993: 102ff). And there are probably other Dark Age graves yet to be identified.

And what of Arthur? Does he lie here? Perhaps the last word ought to rest with J Cuming Walters (1997: 26) who, in a poetic burst, describes a typical August sunset over the Island: “Darkness looms over Tintagel… The black chough wheels about the ruins – the spirit of Arthur, say the people, revisiting the scene of his glory.” Now that the chough, after half a century’s absence, is re-established on Cornwall’s shores, we perhaps need look no further for firm evidence of Arthur’s presence in the land.

And at least the inclement weather doesn’t seem to bother it.

Select bibliography and references

Brian K Davison (1999). Tintagel Castle, Cornwall (English Heritage).

E M R Ditmas (1969). Tristan and Iseult in Cornwall (Forrester Roberts).

Neil Faulkner (2009). ‘What is Tintagel?’. Current Archaeology 227: 23-29.

Alan S Fedrick (transl) (1970). Béroul: The Romance of Tristan (Penguin).

Henry Jenner (1927). “Tintagel Castle in History and Romance”, in Journal of the Royal Institution of Cornwall 22: 190-200, republished in Kelvin I Jones (ed)(1996) King Arthur in Cornwall (Oakmagic Publications).

C Lovegrove (2005). ‘How Igerna conceived Arthur’. Pendragon XXXII No 4: 10-13.

— ‘King Arthur’s Tintagel‘.

J A Nowakowski and C Thomas (1990). Excavations at Tintagel Parish Churchyard, Cornwall, Spring 1990: interim report (Cornwall Archaeological Unit / Institute of Cornish Studies).

C A Ralegh Radford (1939). Tintagel Castle, Cornwall (HMSO).

W M S Russell (2005). “Alcmena and Igraine” Pendragon XXXII No 4: 7-9.

Charles Thomas (1986). Celtic Britain (Thames & Hudson).

— (1993). English Heritage Book of Tintagel: Arthur and Archaeology (B T Batsford).

— (1994), And shall these mute stones speak? Post-Roman Inscriptions in Western Britain (University of Wales Press).

L Thorpe transl (1966). Geoffrey of Monmouth: the History of the Kings of Britain (Penguin).

J C Walters (1906). The Lost Land of King Arthur (Chapman & Hall) re-published in Kelvin I Jones (ed) (1997). Arthur’s Lost Land (Oakmagic Publications).

Joy Wilson (1999). Tristan and Iseult: a Cornish love story (Bossiney Books).

First published in Pendragon XXXVI No 1 (autumn 2008).

[1] Now interpreted as HAVG, referring to Honorius Augustus, Western Roman Emperor from 395 to 423; that is, the original slate dates to around 400 AD, implying an official presence here in the dying days of direct Roman rule, when Tintagel might have been known as Durocornovium (as Charles Thomas postulated in 1986). In 2018 Tom Goskar identified two further names, Tito and Budic scratched on the slate; see also my post ‘Changing History?’.