At the beginning of the 1500s a London grocer called Richard Hill busied himself in compiling a Commonplace Book in which he noted down a number of tales and ballads, possibly for the moral education of his young sons.

Among these “tales and balattis” was the lullaby that we have come to know as The Corpus Christi Carol (though we have no idea of the tune it was sung to). This includes such strange, haunting images that after the text was first published in print in the early 20th century debate arose as to their meaning.

And, because of the image of the bleeding knight, scholars and others began to recall the equally strange and haunting image of the Fisher King in the Grail legends.

The Corpus Christi carol (c 1500)

Lully, lulley, lully, lully, lulley

The faucon hath borne my make away

He bare him up, he bare him down

He bare him into an orchard brown

In that orchard there was an halle

That was hanged with purpill and pall

And in that hall there was a bede

It was hanged with gold so rede

And in that bed there lieth a knight

His woundes bleding day and night

By that bede side kneleth a may

And she wepeth both night and day

And by that bede side there stondeth a stone

Corpus Christi wreten there on

The Oxford Book of Carols, first published in 1928, notes that “the mystical meaning of the fifteenth-century original was … eucharistic” but goes further and suggests that various allusions in this carol (and two other more modern versions) “point to an interweaving of the legend of the Holy Grail”.

John Speirs in the mid-20th century similarly declared the Corpus Christi carol “surely the most original and poignant English rendering of the theme of the crucified Christ” before going on to state that “the inspiration is unmistakably the Grail Myth” (Speirs 1971: 77). Moreover, it “strangely recovers the original significance of the mortally wounded knight (of the Grail romances) as the slain god”.

Finally, Miri Rubin’s view is that the carol presents a “complex and rich picture, accomplished from the weaving of the chivalric imagery of the grail and the hall and the eucharistic Christocentric iconography of suffering” (Rubin 1991: 141).

As we shall see, there can be no doubt as to the Christian imagery inherent in this carol, but as to whether the distinguished academics who associated it with themes from Arthurian romances are justified may be less certain. So what can this and similar carols tell us about medieval religious concepts, their pagan antecedents and their relationship with Arthurian tales? Or do we have here a clear example of what Richard Barber (2005: 363) calls “argument by false association” where if “two acknowledged facts appear to have something in common, they must be connected”?

All Bells in Paradise: mid 19th century

Over yonder’s a park, which is newly begun:

All bells in paradise I heard them a-ring

Which is silver on the outside and gold within:

And I love sweet Jesus above all thing

[three verses]

At the bedside there lies a stone:

Which our blest Virgin Mary knelt upon:

At that bed’s foot there lies a hound:

Which is licking the blood as it daily runs down:

At that bed’s head there grows a thorn:

Which was never so blossomed since Christ was born:

Down in yon forest: early 20th century

Down in yon forest there stands a hall:

The bells of paradise I heard them ring

It’s covered all over with purple and pall:

And I love my Lord Jesus above anything

In that hall there stands a bed:

It’s covered all over with scarlet so red:

At the bed-side there lies a stone:

Which the sweet Virgin Mary knelt upon:

Under that bed there runs a river [flood]

The one half runs water, the other runs blood

At the foot of the bed there grows a thorn

Which ever blows blossom since he was born

Over that bed the moon shine bright

Denoting our Saviour was born this night

Meaning

The imagery of The Corpus Christi Carol is clearly related to its modern analogues, The heron flew east (Scottish, early 19th century), All bells in paradise (North Staffordshire, 1862) and Down in yon forest (Derbyshire, early 20th century). Only Down in yon forest has survived with its music; apart from The heron flew east [1] most of the texts are reproduced above.

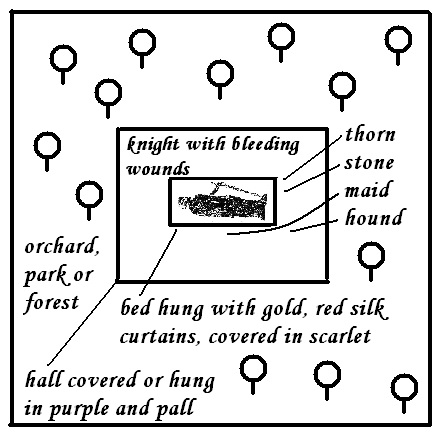

In all of them we have an enclosed area with trees (an orchard, park or forest) in which is found a hall (hung or covered “in purple and pall”). In the hall there is a bed hidden from view with gold or red material. There are incidental details which can vary (a thorn, a stone, a weeping maid, a hound).

As Rubin remarks, The Corpus Christi Carol is simultaneously a lullaby sung by a mother to her baby, a medieval romance, a liturgical text and, above all, a riddle: though the modern texts give no clear answer, at the end of the 1500 text we are explicitly told that the bleeding knight is Corpus Christi, the Body of Christ. Though some of the correspondences are a little ambiguous, it seems that we are invited to identify a church setting, in the middle of which is possibly an altar, on which is placed a liturgical vessel (such as a ciborium or paten) covered over with red or purple cloth (associated liturgically with, respectively, martyrs and penance, especially the period of Lent).

The vessel contains the Body and Blood of Christ (usually commingled during the Communion), but the outward appearance of bread and wine is mystically seen as a wounded knight. The figure can only be Christ: as The Mass of St Gregory (Dürer’s contemporary print illustrating a vision during mass of the wounded Christ in his tomb) shows, we’re meant to be contemplating the meaning of the wafer resting on a paten covering a ciborium or chalice.

The feast of Corpus Christi, instituted in the early 13th century, was the culmination of a long and lasting interest in the doctrine of the Real Presence, especially by lay religious women called Beguines. One, Juliana of Cornillon, had a vision showing a full moon with a blemish, interpreted as a missing feast in the liturgy of the church which Corpus Christi was to fill. Side by side there was an intense devotion to the suffering Christ, with the wounds inflicted during his Passion such as those made by the Crown of Thorns. These concepts kept their spell over the faithful, right up to and including the Reformation.

How does this all relate to medieval stories of the Fisher King, the Dolorous Blow and the Wasteland? Simply put, very little, despite the suggestions of distinguished commentators. Here I would like to postulate that there are three strands of imagery running through the songs, and that these are similar to but not the same as the motifs that contribute to the make-up of the mysterious king of the Grail legends. The strands of imagery in the songs are related to a rural lifestyle (orchard, forest or park, falcon or heron), then to chivalric romance (the hall, the knight, the hound) and finally to religious symbols (the richly-coloured materials, the Blessed Virgin Mary, Corpus Christi): this much is undeniable.

The motifs in the Fisher King story are related to these strands, but not so clear cut. These three motifs in the composite picture of the Fisher King that has come down to us are (1) the king whom we first meet fishing in a boat on a river; (2) the ailing or maimed king whom we meet in the Grail Castle; and (3) the ruler of the wasteland. As we shall see, the three motifs are not universally present in all the Grail stories, and there is not even always an explicit connection between them.

The King, the Blow and the Wasteland

Scholars generally now agree that the Fisher King has no specific Celtic antecedent. Chrétien de Troyes is the first to introduce Perceval (and us) to the mysterious fisherman (Bryant 2006: 35f). Perceval is looking for his mother, and expects to find her on the other side of a fast-flowing river, in what he believes is the Waste Forest. He sees two men in a boat anchored in the middle of the stream, with the one in the bow fishing with a small fish as bait on a line. As there is no crossing for miles, and it is getting late, the fisherman directs Perceval to his own house, which turns out to be more sumptuous than expected. We are later told that because of a disability this “rich fisher king” can’t “manage any other sport” but instead goes fishing in the manner described.

In essence, that is all we learn from Chrétien’s account about the significance of this king’s sport. We might surmise that to see a lord fishing with a line is unusual enough for Perceval to be given an explanation, but due to the romance’s unfinished state we will never know whether Chrétien intended to make more of this motif. He may have meant it to be a reflection of the reality of a disabled ruler’s existence or he may have simply had in mind the injunction given by Christ to Peter the fisherman to leave his profession and become “a fisher of men”, so that Perceval is seen as an emerging Christian. Or, as Perceval is self-evidently a literary fairytale, the fisherman may merely be a typical fairytale helper, such as one sees in profusion in the Breton story Peronnik.

Chrétien however gives us real no hint that the there may be an esoteric meaning to the fisherman’s pastime: Wilson suggests that Chrétien “may well have given the king the occupation of fisherman, since he might seem in need of an occupation … and there are few so suitable for a crippled king living by a river” (1988: 135).

There have been bold attempts to link this figure with pagan heroes or deities (the classical Orpheus, for example, or Nodens in Roman-British mythology). John Grigsby (2002: 7) believes that “at heart the Grail legend is connected to both sacrifice and a lost mystery rite … that had originated not in the Classical world but in the Celtic”. At the root of this latter approach is what later became known as the Dolorous Stroke or Blow.

Chrétien recounts how Perceval is told that the fisherman “was wounded in a battle and completely crippled, so that he’s helpless now, for he was struck by a javelin through both his thighs” and “can’t mount a horse” (Bryant 2006: 41). For any ruler this was potentially a disaster, especially when it came to waging war.

That this injury through the thighs was a euphemism is clear from vivid accounts of the Battle of Hastings: Harold was stabbed, beheaded, disembowelled and had his “leg” cut off at the thigh and carried away: this last action was so censured by Duke William that it can only refer to his genitalia being removed (Wood 1981: 228). Such brutality was, sadly, so commonplace that we could accept Chrétien’s account as merely reflecting reality, if it were not for the version that Robert de Boron produced of Chrétien’s Perceval.

Robert’s elaboration of Chrétien’s story included giving the anonymous king a name as well as a title: before meeting him Perceval is told that he is “entered upon the quest of the Grail that Bron your grandfather has in keeping, he who is called in many countries the Fisher King” (Skeels 1966: 46). It is the combination of name and maiming that, some suggest, most clearly link Robert’s grail story with Celtic mythology.

In Branwen, the second Branch of the Mabinogion, Bendigeidfran (“Blessed Brân“) is wounded in the “foot” by a poisoned spear in a battle with the Irish. Mac Cana and others argue that this detail, plus a probable reference to Brân as Morddwyd Tyllion (“The Pierced Thigh”), point to this being “a perfect antecedent to the wound in the groin or the thighs … which incapacitated Chrétien de Troyes’ Fisher King and several other Arthurian characters whom scholars derive from the Welsh Brân” (Mac Cana 1958: 163-4).

Many will remember Malory’s description of the Dolorous Stroke (or Blow) with a spear in ‘The Knight with the Two Swords’: “For the dolerous stroke [Balin] gaff unto kynge Pellam thes[e] three contreyes ar[e] destroyed.” In Malory’s lifetime the incapacity of kings did put the good governance of the country in jeopardy, so this tale of a wasteland (une Terre Gaste) did have resonance for his audience. Now ‘Pellam’ may well be a 15th-century version of Robert’s ‘Bron’ and of the Welsh ‘Brân’, and so one may well be looking for a causal connection between the Stroke and the Wasteland that followed all the way back to early Welsh mythology.

However, such a link may not always be present – in the third Mabinogion Branch, Manawydan, Dyfed becomes a wasteland not through an unfortunate blow but through an enchantment brought about by motives of revenge – so it must not be assumed to be a given in the grail tales.

Despite all these provisos, there does seem to be a number of overlays on early oral tales: first Chrétien’s romance, then Christian interpretations in subsequent romances, and finally the various modern speculations, some scholarly, some rather more imaginative; and it may well be that there is more to the original oral tales than meets the eye, but for us now those pieces of the jigsaw may be forever missing. Richard Barber’s “argument by false association” seems to be all that we’re left with.

References

• Richard Barber (2005), The Holy Grail: the history of a legend (Penguin).

• Nigel Bryant transl (2006), Chrétien de Troyes: Perceval, the story of the grail (D S Brewer).

• Percy Dearmer, R Vaughan Williams, Martin Shaw (1964), The Oxford Book of Carols (Oxford University Press).

• John Grigsby (2002), Warriors of the Wasteland: a quest for the pagan sacrificial cult behind the grail legends (Watkins).

• Proinsias Mac Cana (1958), Branwen Daughter of Llŷr: a study of the Irish affinities and of the composition of the second Branch of the Mabinogi (University of Wales Press).

• Miri Rubin (1991), Corpus Christi: the Eucharist in Late Medieval Culture (Cambridge University Press).

• Dell Skeels transl (1966), The Romance of Perceval in prose: a translation of the Didot Perceval (University of Washington Press).

• John Speirs (1971), Medieval English Poetry: the non-Chaucerian tradition (Faber & Faber).

• Eugène Vinaver ed (1954), The works of Sir Thomas Malory (Oxford University Press).

• Anne Wilson (1988), The Magical Quest: the use of magic in Arthurian romance (Manchester University Press).

• Michael Wood (1981), In Search of the Dark Ages (BBC Books).

[1] Speirs (1971: 79) gives the refrain as “The heron flew east, the heron flew west, | The heron flew to the fair forest”; he also draws parallels with the rhyme of the children’s game The Key of the Kingdom.

This article, now slightly revised, was first published in Pendragon, the journal of the Pendragon Society, Vol XXXIV No 4 (Summer 2007): 25-28.

Hi there,

I am currently writing an article of “King Arthur & the Holy Grail” and have come across references on Academia by “Mumble” suggesting a pagan Christian Goth who was converted to Christianity.

He writes:

“The relationship of King Arthur to the Byzantine Empire is something akin to that of the missing years of Jesus being spent in India, & the Grand Tour of Europe made by William Shakespeare 1585-87. The evidence for Arthur’s own travels & Gothic heritage lies scattered through the sources, & this paper attempts to place the scraps together to make some kind of cohesive outline of Arthur’s connections to the Byzantine Empire.

In the 12th century, Alain de Lille commented on just how popular Arthur was in the east.

Whither has not the flying fame spread and familiarized the name of Arthur the Briton, even as far as the Empire of Christendom extends? Who, I say, does not speak of Arthur the Briton, since he is almost better known to the peoples of Asia than to the Brittanni, as our palmers returning from the East inform us? The Eastern peoples speak of him, as do the Western, though separated by the width of the whole earth… Rome, queen of cities, sings his deeds, nor are Arthur’s wars unknown to her former rival Carthage. Antioch, Armenia, and Palestine.

There is a definite connection between Arthur & Sicily. The mirages that are said to be seen in Straits of Messina which separate Sicily from the Italian mainland are named ‘La Fata Morgana’ after King Arthur’s sister, Morgan La Fey. Edmund Gardner, in his ‘The Arthurian Legend in Italian Literature’ (1930), translates a Tuscan poem concerning two knights from England, which reads; “We are knights of Britain, who come from the mountain that men call Mongibello (Etna). Long have we stayed there to learn and and the truth concerning our lord, King Arthur, whom we have lost and know not what has befallen. Now we are returning to our native land, to the realm of England.” This clearly places Arthurian troops in Sicily waiting for Arthur. Gardner gives another Sicilian connection, citing Graf’s ‘Artu nell’ Etna’ (Mit, leggende esuperstzioni del medio evo: Turin, 1893) & Caesarius of Heisterbach’s ‘Dialogues miraculorum;

Furthermore:

Then Glewlwyd went into the Hall. And Arthur said to him, “Hast thou news from the gate?”“Half of my life is past, and half of thine. I was heretofore in Kaer Se and Asse, in Sach and Salach, in Lotor and Fotor; and I have been heretofore in India the Great and India the Lesser; and I was in the battle of Dau Ynyr, when the twelve hostages were brought from Llychlyn. And I have also been in Europe, and in Africa, and in the islands of Corsica, and in Caer Brythwch, and Brythach, and Verthach; and I was present when formerly thou didst slay the family of Clis the son of Merin, and when thou didst slay Mil Du the son of Ducum, and when thou didst conquer Greece in the East.

Cuhlwych & Olwen

The sites of many of the places mentioned in the C&O passage above have been lost to modernity. There is enough, however, to show that Glewlwyd was campaigning in Byzantium & beyond. India the Great is India itself, while India the Lesser was Ethiopia. There are also mentions of Africa, Greece & the islands of Corsica. All of these places were theaters of action for the Byzantines, especially during Justnian’s Reqonquista in the 520s & 530s. Salach should be Seleucia, a major Sassanian city on the Tigris. We also know about the Byzantnians driving a certain Godas out of Sardinia, andc their fighting the Hymarites in Arabia (Lesser India) in530. The crucial section for our investigation is when Glewlwyd ells Arhur

, ‘I was present… when thou didst slay Mil Du the son of Ducum.’ Mil Du, son of Ducum, was a Jewish warlord called Dhu Nawas, who was defeated in the Yemen in 527.

According to the Chronicle of John Malalas, the Arthwys sounding Erythius held the title of Patricius in the Byzantine empire, in 527. The same noble title was found in connection with Arthur on a seal at Westminster last seen in the 16th century. In his preface to Sir Thomas Malory’s Le Morte d’Arthur, William Caxton writes, ‘in the Abbey of Westminster, at St. Edward’s Shrine, remaineth the print of his seal in red wax closed in beryl, in which is written “Patricius Arthurus, Brittannie, Gallie, Germanie, Dacie, Imperator.” The mention of Dacia is extremely relevant, being a Byzantine District to the North of Thrace.

A Gothic Arthur:

Arthur’s Byzantine connection could come through the largely unexplored possibly that he was of Gothic descent. The Mabingion tells us Arthur’s brother on his mother’s side was a certain ‘Gormant, whose father was Ricci.’ This means that Igerne would have had children with ‘Ricci,’ who could be Recitach Strabo (d.481), the son of the pro-Byzantne chieftain of the Thracian Goths called Theodoric Strabo. This could at least explain why speaking in 538, Belisarius appears to presume that Britain is populated by Goths. Procipius reports; And the barbarians said: “That everything which we have said is true no one of you can be unaware. But in order that we may not seem to be contentious, we give up to you Sicily, great as it is and of such wealth, seeing that without it you cannot possess Libya in security.” And Belisarius replied: “And we on our side permit the Goths to have the whole of Britain, which is much larger than Sicily and was subject to the Romans in early times. For it is only fair to make an equal return to those who trust do a good deed or perform a kindness.”

Recitach’s father, Theodore Strabo, might be the same Theodoric named in several In several Cornish histories as a sub-king of Dumnonia, in which region lay Tintagel;

RIVIERE, near Hayle, now called Rovier, was the palace of Theodore, the king, to whom Cornwall appears to have been indebted for many of its saints. This Christian king, when the pagan people sought to destroy the trust missionaries, gave the saints shelter in his palace, St. Breca, St. Iva, St. Burianna, and many others, are said to have made Riviere their residence. It is not a little curious to end traditions existing, as it were, in a state of suspension between opinions. I have heard it said that there was a church at Rovier–that there was once a great palace there; and again, that Castle Cayle was one vast fortified place, and Rovier another.

Popular Romances of the West of England collected and edited by Robert Hunt [1903) suggest of course that the two Theodorics may be different men, but what it does do is place a Gothic name amongst the Sub-Roman nobility of Britain, that of Alathar. That there were Goths in the 6th century British nobility can be seen through the son of Arthwys (Arthur). Gwrgi & Peredur were the sons of Eliter of the Great Retinue, son of Arthwys son of Mar, son of Keneu, son of Coel.

Descent of the Men of the North

Gwrgi and Peredur the sons of Elifert died (Annales Cambraie) so, Gurci and Peredur were sons of Eleuther. The name Elifert is the linguistic equivalent of ‘Alathort,’ the name given by Jordanes for a certain Alathar. Thus; Alathar (John of Antioch) = Eleuther (Harleian) Alathort (Jordanes) = Elifert (Annales Cambrae) Alathar was a Gothic general who became the ‘Magister Militum’ of Thrace who fought on the side of Emperor Anastasius in the civil war against Vitalian. That this figure shares a name with Eleuther may indicate they were the same man, but what it does is show once again is a Gothic name within the British sub-Roman nobility. Similarly, Eleuther’s son, Pheredur, also has a Gothic name, Pharas, the Herulian.

In the medieval Grail romances, we see how Peredur spends some time in the Byzantine Empire. By picking apart the variant names Pheredur and its variant, Parzival, we can achieve the correct phonetics contained in ‘PHARAS ERIL. The ‘ph’ of Pheredur while ARAS becomes the ‘arz’ of Parzival and ER: The ‘ur’ of Pheredur and IL the ‘al’ of Parcival. Pharas the Herulian is mentioned by Procopius as fighting for the Byzantine empire.

LikeLike