Portions of this piece were first published in Pendragon, the Journal of the Pendragon Society XIII, No 1 (winter 1979) 11-13, and revised in 2024 to include substantial additions, corrections, notes and updates.

It also includes material from my essay ‘King Arthur’s Glastonbury’, Research into Lost Knowledge Organisation Newsletter No 27 (autumn-winter 1985) 15-18.

Perhaps the best-known work of the Matter of Britain is entitled Le Morte D’Arthur (‘The Death of Arthur’). Malory’s narrative has the inexorable momentum of a Greek tragedy, as befits the subject of this work of fiction, but in fact we can take nothing for granted when we examine the earliest evidence for the death of Arthur – if in fact he ever lived, of course.

“539. The strife of Camlann in which Arthur & Medraut perished…”

So runs an entry in the 10th-century Welsh Annals, though some scholarship suggests that the date should have been calculated as 511.¹ Traditionally Mordred is said to be the treacherous nephew of Arthur, but this terse entry suggests no such thing; rather the reverse, that Arthur and Medraut fought on the same side.

More doubts come with Camlann itself. Romantics place it in Cornwall (by Slaughterbridge on the River Camel) or near the Somerset river Cam. Historians prefer Camboglanna (the Roman fort of Castlesteads on Hadrian’s Wall) which means ‘crooked bank’, as the fort overlooks a bend in the River Irthing.²

With such will-o’-the-wisp documented facts we could well start to believe the statement from the Welsh Stanzas of the Graves, “A mystery till doomsday, the grave of Arthur” – to which we can add William of Malmesbury’s assertion in the twelfth century that “the sepulchre of Arthur is nowhere known.” We will have reason to return to William later.

Memorials

Let’s however start by examining a different kind of evidence. In the fifth to seventh centuries a certain type of memorial stone was in common use in insular Britain; in Wales we have evidence for about 140, in North Britain perhaps a dozen and in the Southwest about 40; and of course the numbers continue to rise.

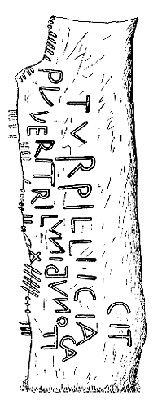

These have inscriptions on them which show they were mostly set up either as tombstones or memorials, and they mention professional people, priests and rulers.

If we could ever find a pillar-stone or slab marked with Arthur’s name we might begin to unravel this mystery.

What would we expect to find? ARTVRI(I), “(The gravestone or memorial) of Arturius” perhaps, maybe with a filiation FILI(I), “son of” added, or a title such as REX, “king”.

A more common formula is (H)IC IACIT, “Here lies”, less often some such phrase as (H)IC IN TVMVLO IACIT, “Here entombed lies”. (In insular Late Roman inscriptions the classical ‘Hic iacet’ ‘Here lies’ often appears in the localised vernacular, the lingua franca, as ‘Ic iacit‘.)

Thus a likely contemporary inscription for Arthur’s gravestone (if he ever had one, indeed, if he ever existed) would be (H)IC IACIT ARTVRIVS REX, perhaps with an additional qualifier SEPVLTVS ‘buried’.

If, however, a memorial was raised some years after his death but before the Saxons arrived at, say, Glastonbury in the 7th century an inscription reading something like this would be possible:

HIC SEPVLTVS IACIT ARTVRIVS INCLITVS REX

(“Here buried lies Arthur the famous king”).

The use of the word inclitus – ‘famous, renowned’ – should not surprise us. Theodoric the Great (died 526) was described as glorississimus adque inclytus rex Theodoricus, “the most glorious and also famous king Theodoric” in an Italian inscription.³ The 7th-century Welsh king called Catamanus (in modern Welsh, Cadfan) was called opinatisimus omnium regum, “most renowned of all kings”, on a stone inscription set up in Anglesey mere decades after his death.⁴

Glastonbury

Where should we begin looking for such a stone for Arthur? The early 12th-century writer Geoffrey of Monmouth placed ‘Cambula’ in Cornwall, where the ‘famous (inclytus) Arthur’ was ‘wounded to death’ and from where he was carried ‘for the healing of his wounds to the island of Avallon.’ Nobody knows where this Avallon was. It seems to have been a kind of Celtic limbo, perhaps associated with apples (afalau in Welsh) – though that etymology is contentious.

Yet in the late 12th century the monks of Glastonbury Abbey apparently knew where to find the body, and because of Ralegh Radford’s excavations in the 1950s it’s been long surmised we know at least roughly where they looked.

In a much later interpolation in The Antiquities of Glastonbury (‘De antiquitate Glastoniensis Ecclesiæ”) – originally written in the 12th century by the usually sceptical William of Malmesbury – we read that

Arthur, the illustrious King of the Britons [was] buried in the Monks Cemetery, between two pyramidal stones, along with his spouse.

As William died half a century before the excavation of Arthur’s grave in or around 1191 we can dismiss this post hoc assertion. Sometime after the middle of the next century a Glastonbury monk, Adam of Domerham, recorded that

the famous king Arthur … had lain … near the Old Church between two pyramids, once magnificently carved.

Giraldus Cambrensis, better known as Gerald of Wales, had already written this account around the turn of the 13th century, soon after the discovery:

Now the body of King Arthur … was found in our own days at Glastonbury, deep down in the earth and encoffined in a hollow oak between two stone pyramids

… In the grave was a cross of lead, placed under a stone … I have felt the letters engraved thereon.

Three principal questions arise: Where was the ‘old church’, vetusta ecclesia? What exactly were these two ‘pyramids’? And what do we know about the lead cross Gerald of Wales handled?

The Old Church

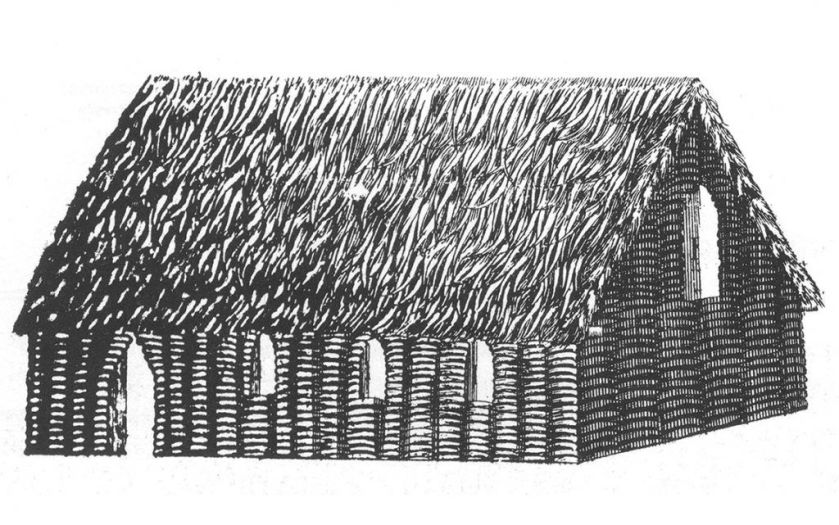

Before the disastrous fire of 1184 the Old Church at the abbey was an ancient wooden structure; it supposedly had the same dimensions as the stone Lady Chapel which was built to replace it (the walls of which are still standing today).

The exact antiquity of this vetusta ecclesia (or lignea basilica, a wooden hall structure constructed from intertwined willow osiers) needn’t concern us just now: we need only note that it’s now assumed to have existed in the post-Roman period, perhaps as early as the sixth or seventh century CE.⁵

Saxon cross shafts

The so-called pyramids appear to have been the shafts of Saxon crosses, like obelisks rising above ground level. First described by William of Malmesbury around 1135 – as recorded in his De Gestis Regum – they were said to be ancient, and carved with figures and names, many barely legible; fragments of such cross shafts have in fact been excavated in the grounds of Glastonbury Abbey, one showing a dragonesque head forming part of an interlace pattern.

Ine, the Saxon king who ruled Wessex 688–726, had enriched Glastonbury with a new stone church, erected to the east of the Old Church. In his reign a cross may have been erected in the monks’ cemetery south of the Old Church: about 26 feet high, in four storeys, it was inscribed with the words CENTWINE | HEDDE EP[IS]C[OPUS] | BREGORED | BEOWARD.

These apparently represent Ine’s predecessor Centwine, King of Wessex 675–685; Hæddi, bishop of Winchester 677–705; Bregored, the last British abbot of Glastonbury (died 669); and either Beorhwald or Berwald another abbot (705–712) or Beortwald or Brithwald the first Saxon abbot, 669–678, and later Archbishop of Canterbury. Some or all of these bodies may have been interred in a mausoleum situated below the cross, later largely demolished in the 10th century during the lifetime of St Dunstan.⁶

Another cross shaft, 28 feet high and in five storeys, seems to have neen sited between the Centwine cross and the Old Church. The lower four storeys contained inscriptions which were transcribed by William early in the 12th century. In the 14th century John of Glastonbury in his Cronica based his description of the taller shaft on William’s earlier description:

On the upper level is a picture of a bishop. On the second is a royal likeness and the words Her, Sexi, and Blisier.

On the third are these names: Wemcrest, Bantomp, Wineweng. On the fourth level: Hate, Wlfred, Eanfled. On the fifth and lowest level is a picture and the inscription: Logior, Weslicas, and Bregden, Swelwes, Hwingendes, Berci.⁷

Interestingly, later Glastonbury writers claimed that St Patrick himself met twelve hermits here in the 5th century, around 425 CE; some of their names have evidently been taken from the names on the shaft. The supposed Dark Age hermits area listed as Brumban, Hiregaan, Bremwal, Wencreth, Banttomeweng, Adelwoldred, Loyor, Wellies, Breden, Swelwes, Hinloernus and Hyn: it’s clear that the names in bold are adapted from the individuals listed in the third to fifth storeys of the taller cross shaft.

Looking at the various medieval lists that were compiled of abbots from the start of the 7th century up to the mid-8th century, one could have great fun trying to match individuals with the garbled names on these inscriptions:

Worgret or Worgrez, Lademund, Bregored, Berthwald (Beortwald), Hemgisel or Hemgislus (Haemgils), Berwald (Beortwald), Albert (Aeldbert), Echfrid (Egfrith), Wealhstod, Cengisle or Cengille (Cynegils), Tumbert or Tunbert, Tica(n) or Tyccea…

It may however be a fool’s errand. Still, none of these names nor the manner in which they’re inscribed corresponds to my suggested reconstruction of the wording on a postulated Arthurian memorial – Hic iacit sepultus inclitus rex Arturius – meaning no-one after the 7th century CE would’ve mistakenly identified his name and honorifics on the Saxon cross shafts.

Inscribed lead cross

What about the lead cross that was placed with the grave? Modern archaeologists point to mortuary crosses roughly contemporary with the Glastonbury exhumation which are possible parallels.

One is from Canterbury where in the 12th century a certain priest called Benedict was interred with an equal-armed leaden cross inscribed with his name and status: + BENEDICTVS SACERDOS.

At Wells Cathedral near Glastonbury the tomb of Giso, who was Bishop of Wells from 1060 to 1088, was in 1979 found to contain a leaden so-called pectoral cross; two of the four splayed arms were slightly elongated, measuring 16.5cm or 6.5 inches in length; one face was lightly incised with an equal-armed heraldic cross potent – displaying crossbars like capital Ts at the four ends – while the back face featured a lengthy Latin inscription taken from the Mass for the Dead.⁸

Now it’s worth looking at the different terms for these crosses. An equal-armed or equal-limbed cross is also known as a Greek cross, as opposed to a Latin cross in which the lower arm is elongated. A mortuary cross is one interred with a body, and thus often made of lead rather than a more precious metal. Finally a pectoral cross as worn throughout the medieval period was one usually suspended from a chain round the neck to rest on the chest; it’s worth noting that in the early medieval period they were as often worn by the nobility as by ecclesiastics, were frequently of gold or silver, were almost invariably equal-armed, and not infrequently buried with their owner.

So we can say that both the Canterbury and the Wells examples were funerary crosses made of lead, but in addition were probably modelled on pectoral crosses, because equal-armed and associated with ecclesiastics. Then what of the Glastonbury example? We can certainly categorise it as funerary — it’s leaden and supposedly excavated from a grave — but we can rule it out as a pectoral cross, being neither of precious metal nor in the Greek form.

In addition it’s what in heraldry is known as a cross fitchy at the foot or fitched at the foot (from French croix fichée). The term, based on Latin fīgere (to fasten, or fix), relates to portable crosses that could be fixed to or hammered into the ground because of a spiked projection at the end of the foot.

I have elsewhere argued (and I’m certainly not the first to do so) that it’s too easy to assume that at the end of the 12th century the abbot and his community, desperate to secure monies for rebuilding the abbey, simply staged Arthur’s burial and disinterment. The letter forms that William Camden copied from it are not exclusively from the 12th century (as on Benedict the priest’s cross from Canterbury, created just a few decades before) but have parallels with examples several centuries earlier. It’s entirely plausible that the monks were acting after being encouraged by a genuine tradition, even if their motives were monetary.⁹

What then was the purpose of the lead cross? Well, from the inscription it seems to me to be a stand-in for a memorial monolith inscribed with a text to indicate to the world at large that the famous king Arthur was buried at a particular spot. This surely suggests a different category needs to be applied in this instance, and a new scenario imagined to account for it.

Motivations

Now we come to the crux of the matter, the purpose of the discovery of the putative grave of Arthur accompanied by an inscribed lead cross in 1191, declared to have been because the monks acted on a tip from a Welsh bard, but later loudly declared to be a fake by reputable historians. Here are the essential planks in the case against Glastonbury Abbey being the legendary monarch’s last resting place.

- According to Gerald of Wales Henry II (reigned 1154–1189) had encouraged the monks to believe Arthur was buried here. His motivation? The desire of the Plantagenet dynasty to bask in an association with Arthurian legend, then very popular, combined with a policy of demoralising the Welsh who held that his grave was unknown because he’d return to lead them to victory.

- After the fire of 1184 had destroyed the Old Church Henry’s royal patronage of the Abbey meant rebuilding could start. But Henry died in 1189, so the monks will have required the touting of some extra special relic to attract pilgrims and rich patrons to the site, so that rebuilding could continue.

- Finding Arthur’s grave would raise their profile, would put paid to the aspirations of Welsh religious houses and political ambitions, and conveniently bring in much needed revenue.

- The new Plantagenet king, Richard the Lionheart, had recently appointed his cousin as abbot of Glastonbury and then named his nephew Arthur, Duke of Brittany (born 1187) as heir to the throne. It was therefore no coincidence that an Arthurian connection emerged soon after Richard’s actions.

- According to the hypothesis, the monks surrounded the pretended grave site with curtains, smuggled in some bones and hair in a boat-like oak coffin, having previously manufactured a lead cross between six and twelve inches long with the Latin text Hic iacit sepultus inclitus rex Arturius as confirmatory ‘proof’ and added in insula Avallonia to clinch Glastonbury’s identification with the traditional Otherworld of the Celts.

- Thus bolstered, the Abbey gained added status and, crucially, much needed funds, all thanks to having ‘faked’ the burial and the exhumation; the evidence of bodies (conveniently Guinevere had also been buried with him) and lead cross suitable additions to the store of fake relics the Abbey had accumulated, and would continue to accumulate.

I’m not going to deny that much of this is a plausible interpretation of such documentary evidence as we have: that the monks ‘faked’ the grave in order to raise funds, much as many religious houses in the Middle Ages paraded manufactured sacred relics to encourage pilgrimage and increase revenue. But being plausible doesn’t make an interpretation the only correct one, and other interpretations may have equal plausibility if the arguments are presented logically.

But what does the archaeology of the site tell us? Unfortunately the history of excavations at Glastonbury Abbey in the 20th century is disappointing: conducted piecemeal by a series of different dig directors, there was only one intermediate report published, with no overall assessment of the archive and the finds until well into this century. The single published report was by Courtenay Arthur Ralegh Radford, and his conclusions were based on his deep interest in Early Christianity in Britain.

Archaeology

In the 1950s and 60s Raleigh Radford conducted a series of excavations at the Abbey, including in the area of the ancient cemetery.¹⁰ It was here that he declared he’d discovered where Arthur had been buried, only to be disinterred by the monks at the end of the 12th century.

Radford’s reconstructed sequence of events seems to have been this. Before the 7th century the bodies of a tall man and of a blonde woman were buried in the ancient cemetery of the Celtic monastery variously named as Ynysvitrin or Yneswitrin. ‘Known to be a British appellation’, Yneswitrin has been interpreted either as the island of an unknown saint (Witrin or Gutrin?) or as the Glass Island (compare Latin vitrum and Welsh gwydr, ‘glass’). However, Professor Roberta Gilchrist and a research team from the University of Reading believe that “several details of Radford’s interpretation of the early monastery are challenged by reassessment of the archive, including the existence of a pre-Christian ‘British’ cemetery and the discovery of Arthur’s grave.”¹¹

Radford claimed to have discovered a Christian ‘British’ cemetery, a Saxon cloister that was believed to be the earliest in England, as well as the site of King Arthur’s grave, allegedly located by the monks in 1181.

However this latest analysis disputes these findings, with the graves Radford judged to be ‘Dark Age’ shown to be later than the Saxon church and cemetery. Additionally the site of Arthur’s ‘grave’ was revealed to be a pit in the cemetery containing material dating from the 11th to 15th centuries, with no evidence linking to the era of the legendary King Arthur and Queen Guinevere.¹²

However what the team also drew from their re-assessment, along with the application of modern techniques for investigating and dating material, was important new evidence confirming “that there was high-status occupation at Glastonbury in the 5th or 6th centuries, long before the first monastic foundation was documented.” This evidence included LRA1 (Late Roman amphora) pottery sherds such as that found in other high status sites like Tintagel and South Cadbury, dated by radiocarbon analysis from between the middle of the fifth century to the middle of the sixth.

Though Professor Gilchrist adds that it’s currently impossible to determine whether this was associated with “a religious community, or a high status secular settlement engaged in long-distance trade,” the distribution of the eastern Mediterranean material found at mainly secular sites along and up the western coast of Britain may indicate Glastonbury’s likely status around 500 CE as another high status locale.

However, there is also evidence for a north-south oriented post-Roman timber structure, roughly eight by four metres, to the east of the later monks cemetery, its plan determined by a series of ten or so post-pits. The well-trodden floor containing fourteen fragments of the East Mediterranean amphorae; the hall survived until the 8th or 9th centuries. The relation the later Saxon monastery had with this timber hall seems to parallel what excavations (also by the University of Reading) at the royal monastery at Lyminge in Kent have revealed, “that a high-status hall complex was the precursor to the Anglo-Saxon monastery.”

Conclusions

Whether any conclusions can ever be drawn from an iconic site like Glastonbury with its huge weight of expectations, I think a tentative summary may be in order just now from what we know and what we may conceivably speculate about the ‘Dark Age’ period at this spot.

First, we know that before the Saxon monastery was, according to Anglo-Saxon charters, established in the late 7th century there was at least one post-Roman timber hall, 8 by 4 metres in size, prestigious enough for Mediterranean wine and oil jars to have been brought in, used and discarded.

After a Saxon hierarchy established itself in the area and a monastic community founded, a wattle church around 30 metres in length and 7 or so metres wide was in all likelihood built to the northwest, with the area to the south established as the monastic cemetery. Here later were erected two memorial crosses with the names of 7th and 8th century ecclesiastics of high status.

Why was this site accorded such regard that Saxon royal patrons endowed it and some of its abbots went on to become bishops? Was it because there was already a high status burial here, a British chief whose memorial stone declared that as the “famous king” Arthur he was interred here?

And when in the tenth century St Dunstan raised the level of the cemetery, erecting a retaining wall to the south, was the crude monolith replaced with a lead plaque in the shape of a fitched cross, inscribed with some of the ancient text? And did some lingering tradition two centuries later encourage the digging of a pit which, over time, scraps of material from the 11th to the 15th century easily slipped?

Surely this is as plausible a scenario as simply asserting 12th-century monks simply faked any old cross out of lead from the nearby Mendip Hills?

¹ Leslie Alcock, 1971. Arthur’s Britain.

² Camboglanna was long identified with Birdoswald, leading Alcock to suggest an emendation to Cambolanda or ‘crooked enclosure’ to fit more with the Birdoswald topography. Research since the 1970s has identified Castlesteads as the actual site of the named fort; that it overlooks a bend of the river Irthing helps confirm its etymology from Brythonic cambo- (meaning curved or crooked) and –glanna (a stream or river bank). The fort is also skirted by the Cambeck, the stream feeding into the Irthing which includes the element cam-, cognate with modern Welsh cam (‘crooked’).

³ In the early 6th century the Roman senator Basilius Decius, in one of what are called “a series of private inscriptions erected along the Via Appia” in and out of Rome, termed Theoderic “our lord, the most glorious and famous king, conqueror and earner of triumphs” (dominus noster gloriosissimus adque inclytus rex Theodericus, victor ac triumfator). [Jonathan J Arnold, 2008. ‘Theoderic, the Goths, and the Restoration of the Roman Empire’ (doctoral submission for the University of Michigan): 75. https://deepblue.lib.umich.edu/bitstream/handle/2027.42/60883/jjarnold_1.pdf

⁴ V E Nash-Williams, 1950, The Early Christian Monuments of Wales. University of Wales Press, 55-7.

⁵ C A Ralegh Radford, 1968, ‘Glastonbury Abbey’ in Geoffrey Ashe, The Quest for Arthur’s Britain. Pall Mall Press, 119-138, illustrations 94-99. Philip Rahtz, 1993, English Heritage Book of Glastonbury. B T Batsford, 71-3.

⁶ Frank Lomax transl, 1908, The Antiquities of Glastonbury by William of Malmesbury. JMF Books, 1992: 60-1.

⁷ James P Carley, 1985. The Chronicle of Glastonbury Abbey. An edition, translation and study of John of Glastonbury’s Cronica sive Antiquities Glastoniensis Ecclesie. The Boydell Press. 62–3.

⁸ Warwick Rodwell, 1980. Wells Cathedral: Excavations and Discoveries. The Friends of Wells Cathedral. — 1989. English Heritage Church Archaeology. B T Batsford. 18–19.

⁹ Chris Lovegrove. ‘Arthur’s Cross?’ An earlier version appeared in Pendragon, the Journal of the Pendragon Society, in late 1997. https://pendragonry.wordpress.com/2024/03/09/cross1/

¹⁰ C A Ralegh Radford. ‘Glastonbury Abbey’ in Geoffrey Ashe, The Quest for Arthur’s Britain. Pall Mall Press, 1968; C A Ralegh Radford and Michael J Swanton, 1975. Arthurian Sites in the West. University of Exeter. 39–45.

¹¹ The quotations come from various University of Reading research papers and commentaries including

- Roberta Gilchrist. ‘Glastonbury Abbey: the archaeological story’ in Current Archaeology 320 (November 2016), 18-27. https://archaeology.co.uk/articles/features/glastonbury-abbey.htm

- University of Reading, Trustees of Glastonbury Abbey (2015). Glastonbury Abbey: Archaeological Excavations 1904 – 1979 [data-set]. https://archaeologydataservice.ac.uk/archives/view/glastonbury_ahrc_2014/

- ‘Glastonbury Abbey archaeology’ https://research.reading.ac.uk/glastonburyabbeyarchaeology/

¹² Only Gerald of Wales describes the lead cross as having the additional phrase “with Guinevere his second wife”. The Latin of his De Instructione Principum (1193–9) includes the phrase ‘cum Wenneveria uxore sua secunda’. Noteworthy for Guinevere’s name being rendered Wenneveria, Gerald’s spelling reminds us that on the archivolt of the Porta della Pescheria, the north portal of Italy’s Modena Cathedal, Arthur’s queen is inscribed as Winlogee. All of which begs the question: Did Gerald interpret the inscription Wineweng on one of the pyramids as the monarch’s second wife? — Record xxvi in E K Chambers (1927), Arthur of Britain. Sedgwick and Jackson, 1966: 268–271.